In

Greek mythology, Achelous (English, pronounced

/ækɨˈloʊəs/;

Greek: Ἀχελῷος (Achelōos)) was the patron deity of the "silver-swirling"

[1] Acheloos River, which is the largest river of Greece, and thus the chief of all river deities, every river having its own river spirit. His name is pre-Greek, its meaning unknown. The Greeks invented etymologies to associate it with Greek word roots (one such popular etymology translates the name as "he who washes away care"). However, these are etymologically unsound and of much later origin than the name itself.

Origin

Some sources say that he was the son of

Gaia and

Helios,

[2] or Gaia and

Oceanus.

[3] However, ancient Greeks generally believed with Hesiod

[4] that

Tethys and

Oceanus were the parents of all three thousand river gods.

Homer placed Achelous above all, the origin of all the world's fresh water.

[5] By Roman times, Homer's reference was interpreted as making Achelous "prince of rivers".

[6]Others derived the legends about Achelous from Egypt, and describe him as a second

Nilus. But however this may be, he was from the earliest times considered to be a great divinity throughout Greece,

[7] and was invoked in prayers, sacrifices, on taking oaths, &c.,

[8] and the Dodonean

Zeus usually added to each oracle he gave, the command to offer sacrifices to Achelous.

[9] This wide extent of the worship of Achelous also accounts for his being regarded as the representative of sweet water in general, that is, as the source of all nourishment.

Mythological tradition

Achelous was a suitor for

Deianeira, daughter of

Oeneus king of

Calydon, but was defeated by

Heracles, who wed her himself.

Sophocles pictures a mortal woman's terror at being courted by a chthonic river god:

'My suitor was the river Achelóüs,

who took three forms to ask me of my father:

a rambling bull once, then a writhing snake

of gleaming colors, then again a man

with ox-like face: and from his beard's dark shadows

stream upon stream of water tumbled down.

Such was my suitor.' (Sophocles, Trachiniae)

The contest of Achelous with

Heracles was represented on the throne of

Amyclae,

[12] and in the treasury of the

Megarians at

Olympia there was a statue of him made by

Dontas of cedarwood and gold.

[13] On several coins of

Acarnania the god is represented as a bull with the head of an old man.

[14]The

sacred bull the

serpent and the

Minotaur are all creatures associated with the Earth goddess

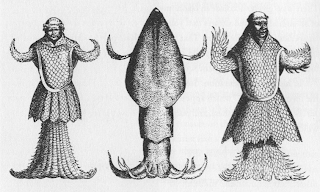

Gaia. Achelous was most often depicted as a gray-haired old man or a vigorous bearded man in his prime, with a horned head and a serpent-like body. When he battled Heracles over the river nymph Deianeira, Achelous turned himself into a bull. Heracles tore off one of his horns and forced the god to surrender. Achelous had to trade the goat horn of

Amalthea to get it back.

[15] Heracles gave it to the

Naiads, who transformed it into the

cornucopia. Achelous relates the bitter episode afterwards to

Theseus in

Ovid's

Metamorphoses.

[16] Sophocles makes

Deianeira relate these occurrences in a somewhat different manner.

[17]The mouth of the Achelous river was the spot where

Alcmaeon finally found peace from the

Erinyes. Achelous offered him

Callirhoe, his daughter, in marriage if Alcmaeon would retrieve the clothing and jewelry his mother

Eriphyle had been wearing when she sent her husband

Amphiaraus to his death. Alcmaeon had to retrieve the clothes from King

Phegeus, who sent his sons to kill Alcmaeon.

Ovid in his

Metamorphoses provided a descriptive interlude when

Theseus is the guest of Achelous, waiting for the river's raging flood to subside: "He entered the dark building, made of spongy pumice, and rough tuff. The floor was moist with soft moss, and the ceiling banded with freshwater mussel and oyster shells."

[18] In sixteenth-century Italy, an aspect of the revival of Antiquity was the desire to recreate Classical spaces as extensions of the revived

villa. Ovid's description of the cave of Achelous provided some specific inspiration to patrons in France as well as Italy for the

Mannerist garden

grotto, with its cool dampness,

tuff vaulting and shellwork walls. The banquet served by Ovid's Achelous offered a prototype for Italian midday feasts in the fountain-cooled shade of garden grottoes.

At the mouth of the Achelous River lie the

Echinades Islands. According to Ovid's pretty myth-making in the same Metamorphoses episode, the Echinades Islands were once five nymphs. Unfortunately for them, they forgot to honor Achelous in their festivities, and the god was so angry about this slight that he turned them into the islands.

Achelous was sometimes the father of the

Sirens by

Terpsichore, or in a later version, they are from the blood he shed where Heracles broke off his horn.

[19]In another mythic context, the Achelous was said to be formed by the tears of

Niobe, who fled to

Mount Sipylon after the deaths of her husband and children.

In Hellenistic and Roman contexts, the river god was often reduced to a mask and used decoratively as an emblem of water, "his uncut hair wreathed with reeds".

[20] The feature survived in Romanesque carved details and flowered duruing the

Middle Ages as one of the Classical prototypes of the

Green Man.